The tadpole in your brain

Chris draws in his sketchbook every day: on hikes in the woods, on walks in the city, on airplanes, subways, buses and trains; in church, in hotel rooms, on work trips, on the beach, on family vacations, at the dining room table, in a crowded café.

In fact, there is almost no circumstance that keeps him from his sketchbook. It’s no wonder his neck gets cramped and his pen hand is starting to look gnarled.

“Why and how do you keep going?” I wanted to know.

“It settles me.”

“But how does it feel to do it? Is it fun? A chore? Is it work? Is it play?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “It’s calming.”

He was heading into the other room to work on his young adult novel but paused to think. “It’s like shooting hoops if you’re a basketball player. Maybe it’s how Stephen Curry feels when he shoots hoops during practice."

He added, "Of course, I’m no Stephen Curry.”

“Who is Stephen Curry--?” I said.

But he was gone.

[interlude to Google Stephen Curry]

Stephen Curry’s dad says the key to expertise is: "Repetition. You have to have the confidence you can do it, and that only comes by putting in work, and then doing it when the game’s on the line.”

Last year a New York Times article called "This is Your Brain on Writing" caught my eye. Neuroscientists used fMRI scanners to track the brain activity of creative writers. Professionally trained writers showed similarities to people skilled at other complex actions, like music or sports.

“A novelist scrawling away in a notebook in seclusion may not seem to have much in common with an NBA player doing a reverse layup on a basketball court," wrote the author. “But if you could peer inside their heads, you might see some striking similarities in how their brains were churning.”

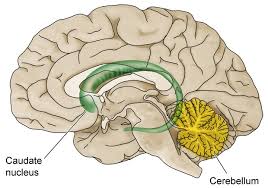

“Deep inside the brains of expert writers, a region called the caudate nucleus became active. In the novices, the caudate nucleus was quiet."

A center for learning and memory, the caudate nucleus looks like a tadpole in the center of the brain, and plays an important role in the skill that comes with practice.

A biology major in college, Chris only started sketching regularly after college in his mid-20s, when we were housemates in Ann Arbor more than 35 years ago. We made a pact to sketch daily. He kept the pact and went on to become an illustrator, ditching medical school at the extreme-angst-filled last minute, the morning of registration. I did not keep sketching and channeled my love of art into making teaching materials for my elementary school classroom, before taking up writing in my mid-30s.

When we first learn a skill we use a lot of conscious effort, the Times author wrote. “With practice, those actions become more automatic...”

I certainly experienced this as a new teacher. Learning how to teach and manage a class happened imperceptibly as I put time in, day after day, year after year.

Knowing I improved back then gives me hope now when I feel hopeless about the daunting task of writing a book.

“Stephen Curry is revolutionizing the game of basketball,” Chris said emerging from the other room.

I know. And I want a little of that Stephen Curry action.

Practice is the key to revolution.